With the wind of change definitely blowing schools towards digital learning and teaching, many schools may be feeling anxious about how to build digital skills into the curriculum and looking for some straightforward approaches and resources.

During our sleuthing to identify free or low cost resources that are available to support schools, we came across Apps for Good. Apps for Good is a charity which provides a free app design course to schools and is targeted at pupils aged 10-18 years.Their resources are used all over the UK with most interest coming from London and Scotland.

We arranged a Skype call with Emily and Natalie from Apps for Good, just to see if it was the kind of project we could recommend to schools as part of our work, and we were really impressed. The resources are mapped to the Scottish and English curricula, and teachers looking to get involved don’t need to be particularly ‘techy’, as training and support is provided.

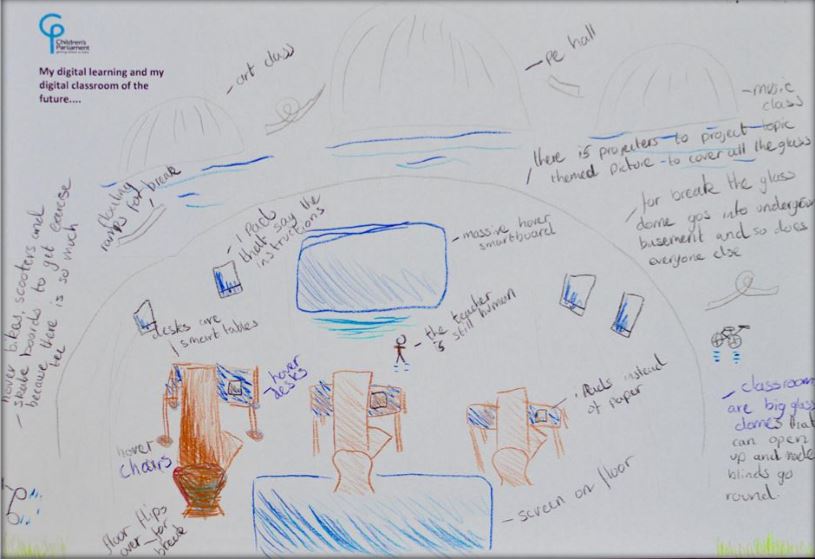

Interested schools are asked to take on an app development project. Groups of pupils are asked to think about a problem affecting their community and have to generate an idea for an app which could help with this. Initially this is a problem solving challenge. The pupils form a start-up company and develop a prototype of their app using coding skills.

As we mentioned above, there is a programme offering online training that supports teachers through every stage. The training could be worked through in advance but from speaking to people, it seems that many do it as they are going along. The altruistic aspect to the project ticks so many boxes for teachers looking for a really meaningful way to introduce a technologies project to their classes, and the end products have a chance to go forward for Apps for Good awards each year, with the winning team having their app made commercially available.

We like these resources as they offer a ready made framework, with support, that still allows for a huge amount of personalisation and creativity. Any teachers interested in finding out more can sign up here at their website – we already have!